Markup and HTML

CMPT 165, Fall 2019

Markup Languages

A markup language is a way to describe a document, using only plain (unformatted) text.

Whatever we want to say about the content (what it is, formatting, etc) has to be expressed using plain text.

Markup Languages

An example markup language: wikitext.

Wikitext is simple markup language meant to be fast to learn and produce pages with relatively simple formatting. Wikipedia pages are generated from their wikitext dialect.

Markup Languages

Some example wikitext markup:

Line with an '''important''' word. * point one * another point

When displayed that would look like:

Line with an important word.

- point one

- another point

Markup Languages

But we aren't really concerned with wikitext: it's just a good first example of markup.

The markup language we care about is HTML.

Markup Languages

To make a markup language work, we need somewhere to write the markup language code, and some way to turn that into our final output.

Text Files

HTML (and CSS and JS) files contain only characters: no formatting. That is, they are text files.

Other things that are text files: CSV, markdown, Java, Python (and every other programming language).

Text Files

Creating text files is done in a text editor. These are simple tools that let you enter characters, and are designed for working with programming languages and other plain text files.

Different text editors will display text with different fonts/colours: those don't matter since those aren't part of the file. All that ends up being saved are the characters you type.

Text Files

You can find links to download a text editor in the Study Guide. You'll need one. Word processors are not appropriate.

Basically: every text editor does fundamentally the same job. Find one you like.

Text Files

HTML files are text files, saved with the extension .html.

As long as you name the file something.html, it will be treated as HTML.

HTML Tags

Here are the basic contents for an HTML file:

<!DOCTYPE html> <html> <head> <meta charset="UTF-8" /> <title></title> </head> <body> </body> </html>

HTML Tags

We can type (or copy-and-paste) that into a text editor, save as a .html file, and open it to see a blank page in the web browser.

HTML Tags

The code in the

are HTML tags.<…>

Tags come in opening and closing pairs, like

(except for a few we'll talk about later).<body>…</body>

HTML Tags

The stuff between the tag's opening and closing are the contents.

The opening tag + contents + closing tag form an element.

HTML Tags

Demo:

- Create an HTML file with the contents above. Open in a browser.

- Fill in the

<title>. Reload. - In the

<body>, add a<p>element with some text. Reload.

HTML Tags

Notice that all tags are nested

together so that one is either entirely inside or outside another. They cannot partially overlap.

These are one element inside another; one element after another; opening/closing tags incorrectly overlapped.

<x><y></y></x>

<x></x><y></y>

<x><y></x></y>

Basic Tags

Let's look at the things we saw in that first .html file…

<!DOCTYPE html>: The document type declaration which indicates that we're using HTML5. Not actually and HTML tag, but some meta-information about the document.<html>…</html>: the document tag that contains the entire HTML page. Starts first and ends last.

Basic Tags

<head>…</head>: information about the page. It will only contain the <meta> and <title> for now.<meta charset="UTF-8" />: thecharacter encoding

for the file, which indicates how the text is encoded into bits. For us, this tag will always appear exactly like this.

Basic Tags

<title>…</title>: The main title for the page. Used in the browser window's title bar, for bookmarks, etc.<body>…</body>: The actual content of the page. Displayed in the main part of the browser window.- And there are many more…

More Tags

Those tags will be on every page, arranged just like that.

But, we'll need some more tags to put actual content on our page…

More Tags

<h1>: the main heading on the page. Should probably be exactly one on every page, with the same text as the<title>.<p>: a paragraph. Should be used to enclose each paragraph on the page.

More Tags

<em>: emphasized text. Part of a paragraph (or heading or similar) that you want to give emphasis: important words.<ul>: an unordered list. A bulletted list where the order of items isn't important. Can contain only list items.<li>: a list item. Must go in a<ul>(or other list structure).

More Tags

Now we have enough to recreate the Markdown example from earlier in HTML:

<p>Line with an <em>important</em> word.</p> <ul> <li>point one</li> <li>another point</li> </ul>

More Tags

Notice that all of the formatting must be done with HTML (and later CSS). That is, a line break in the HTML code has no effect on the browser display.

Meaning in HTML

If you look in the HTML reference we're using (or any good HTML documentation), you'll see that the HTML tags are defined by their meaning not appearance.

e.g. <em> is described as like emphasized text

, not italics

.

Meaning in HTML

When choosing tags for content, pay attention to the meaning of tags, not what they look like. We'll make our content look the way we want later.

Attributes

The <meta> element we used in the first HTML page we had:

<meta charset="UTF-8" />

What's the charset="UTF-8" part? None of the other tags had that.

Attributes

<meta charset="UTF-8" />

Here, charset is an attribute. Attributes change the behaviour or meaning of an element.

Attributes have a value: UTF-8 in this example.

Attributes

Another example: there is an <abbr> tag to indicate abbreviations.

<abbr>SFU</abbr>

… but it's not very interesting to say that this is and abbreviation. We'd also like to specify what it's an abbreviation for.

Attributes

The title attribute can be used with <abbr> to give the full expansion of the abbreviation:

<abbr title="Simon Fraser University">SFU</abbr>

Browsers generally show the title as a tooltip if you mouse-over the text: SFU.

Attributes

Another example: the lang attribute can be used on any element to specify the natural language of the content.

There are language codes for (every?) language that you're likely to need.

Attributes

For example, we probably should start every page with this document tag, because we're writing English:

<html lang="en">

This will let search engines correctly categorize the page, let the browser offer appropriate automatic translations, etc.

Attributes

If we switch languages somewhere, we can specify that as well.

<p>He demanded <q lang="fr">Quoi?</q> and I was shocked.</p>

Links

The <a> tag is used to create a link, and the href attribute gives the destination.

<a href="http://www.sfu.ca/">Simon Fraser University</a>

Links

<a href="http://www.sfu.ca/">Simon Fraser University</a>

The value for href is a URL. More later about what values can go there (besides complete absolute URLs).

Empty Tags

There was one other weird thing about our meta tag: it didn't seem to be closed:

<meta charset="UTF-8" />

i.e. there was no </meta> anywhere.

Empty Tags

<meta charset="UTF-8" />

The <meta> tag is an empty tag: one that has no contents.

Since it's empty, it must be closed right away. The

is how we will specify that. It's a signal that the tag is closing now and there are no contents/>

Empty Tags

Older versions of HTML allowed you to explicitly close it right away, but this is not allowed in HTML5:

<meta charset="UTF-8"></meta>

… but this is probably the right way to think about it: a tag that closes as soon as it opens.

Empty Tags

Another empty tag: <img /> which is used to insert an image onto a page.

<img src="group.jpg" alt="a group of people" />

The src attribute is used to give the location where the image can be found. In this case, a file in the same directory as the .html. (Also a URL: again, more later.)

Semantic Markup

As we said: HTML tags focus on the meaning or purpose or type of content they hold.

HTML is a semantic markup language. Semantic: to do with meaning.

Semantic Markup

Everything we have expressed in HTML has been semantic: <p> = paragraph, <h1> = level-1 heading, <em> = text that's emphasized, etc.

Semantic Markup

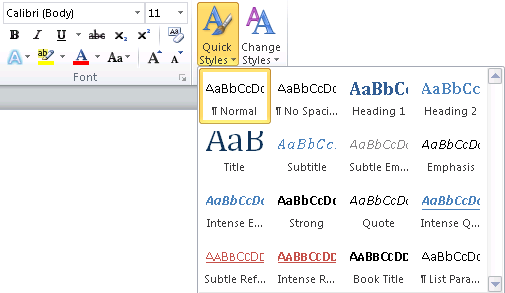

The opposite: visual or presentational markup, as you would often use in MS Word or similar, where you specify bold

or 16 pt font

. Word's styles

are generally semantic.

Semantic Markup

When writing HTML, your job is to worry about the meaning, not the appearance, of the content.

Describe the meaning of the content you have as best possible with the tags available. Pay attention to the meanings given in the reference.

Semantic Markup

We will worry about appearance later with CSS.

CSS is where you can express things like all

.<p> elements should appear with font X, left-justified, red

Semantic Markup: Why?

Why bother with a semantic markup language and another layer for presentation?

This should make it easier to maintain and update the site: if we want every <p> to look different, just update one thing the CSS.

Semantic Markup: Why?

Semantic markup should help search engines: they can extract a lot of meaning from just the markup and better categorize your pages.

Semantic Markup: Why?

It will make it easier to adapt pages to different situations.

For example, on a mobile browser, you might want a different font size, or arrangement of the content. We can express this in CSS, but the semantic content doesn't change: a heading is still a heading.

Example Page

Let's put together a more realistic example: we will use HTML to mark up a recipe.

Parts of the page we need to decide on markup for: serving size (serves 4

), introduction (This is a recipe adapted from my seriouseats.com…

, etc), ingredients, steps.

Example Page

Things I expect to do in the demo:

- Section headings as

<h2>s. - Cite the recipe source with

<cite>s. - Add

<section>s to identify parts of the page.

Results will be posted on the course web site.

Distinguishing Tags

Two problems are going to start happening as we start making real pages and trying to match meaning to markup.

- different kinds of paragraphs, sections, etc;

- content that doesn't match the meaning of tags in HTML.

Distinguishing Tags

For (1), we will want to make them look different later with stylesheets.

e.g. a list that is the table of contents, vs the recipe steps. Both are (ordered) lists, but we might want to style the intro and servings differently.

Distinguishing Tags

We can distinguish instances of the same tag with class or id attributes. Both attributes let you refine the meaning of tags.

<p id="serving">Serves four.</p>

The value for class and id can be any word we want: here, we're suggesting that this paragraph contains something about servings

.

Distinguishing Tags

In this example, we are indicating that there is something different about the last list item:

<ol> <li>Combine ingredients</li> <li>Bake until done.</li> <li class="optional">Garnish.</li> </ol>

Distinguishing Tags

The word optional

suggests (to people, not the browser) how it's different.

In any case, the value for class and id should be a meaningful word.

Distinguishing Tags

The difference: an id value must be unique on a page.

We can have multiple things with class="optional" on a page, but never more than one id="serving" per page.

Distinguishing Tags

You should choose appropriately: if it's a piece of content that will only occur once, use id. Otherwise, class.

We will (soon) be able to use class and id to select certain tags for appearance changes in CSS.

Generic Tags

We solved one of the problems we were having above (tags not specific enough), but not content that doesn't match the meaning of tags in HTML

.

How do we handle content that doesn't match any of the tags in HTML?

Generic Tags

First step: have a good look in the HTML Reference: there might be a tag you didn't know about and will work.

e.g. maybe we want to highlight the quantities of ingredients (2 cups

) from the item (flour

). I can't find any tag I think is relevant.

Generic Tags

But if still nothing fits, there are two generic tags that can be used: <div> and <span>.

These have no meaning on their own and should be given one by a meaningful class or id.

Generic Tags

So our example might get markup like:

<li><span class="quantity">2 cups</span> flour</li>

Generic Tags

The difference: <div> is block-level content (or flow content).

That is, it can go inside the <body> directly, and is generally presented below any previous content. Other block-level tags we have seen: <h1>, <p>, <ul>.

Generic Tags

The <span> is inline (or phrasing) content: it goes inside a block-level tag and is generally beside the next/previous content.

Other inline tags we have seen: <em>, <abbr>, <a>, <q>, <img>.

Generic Tags

General rules for HTML:

- Block-level content goes inside the

<body>and (sometimes) other blocks. - Text and inline content goes inside blocks.

Generic Tags

Another example: suppose we want a collection of social media links like this:

Follow us:

First, consider existing tags for the job: maybe <p> or <section> or <footer>? No, not really.

Generic Tags

So, we reach for a generic tag: this is probably block-level content, so <div>, with an appropriate class.

<div class="social">Follow us: <a href="http://twitter.com"><img src="twitter.svg" alt="Twitter"></a> ⋮ </div>

Generic Tags

Summary:

- Start by looking for an existing tag that has a matching meaning.

- If there isn't one, a generic tag.

- Give a

classoridvalue that suggests some meaning (maybe for any tag, but definitely for a generic tag).

Validating HTML

We have heard many rules about HTML. e.g.

- Tags must be closed.

<ul>must contain only<li>s.- Inline content inside block-level.

But what if we get something wrong?

Validating HTML

The web browser will not tell us: it will do its best to display broken HTML, so it works

on as many pages as possible.

But don't really know if the next browser will “correct” our mistakes the same way. Will our site be horribly broken in another browser? What about when Google tries to index it?

Validating HTML

Solution: actually write correct HTML. If the browser isn't going to give us feedback when we make a mistake, we need something else for that.

An HTML validator will take our HTML and check against the rules of HTML.

Validating HTML

We can use the HTML validator online by going to https://validator.w3.org/.

If our file has been uploaded, we can give its URL. If not, we can upload the file from our computer or copy-and-paste the code from the text editor.

Validating HTML

Expectation from now on: any HTML you produce for the course should pass the validator without errors.

(Warnings are okay, but it's probably not a bad idea to fix them.)

The Robustness Principle

An overall principle for any computer system where two things have to communicate: the robustness principle:

Be conservative in what you do, be liberal in what you accept from others.

The Robustness Principle

Web browsers are holding up their end of the robustness principle by doing their best with not-quite-right HTML: be liberal in what you accept

.

But if we (as HTML authors) rely on that behaviour, we're taking a risk that the next tool won't handle our mistakes the same way.

The Robustness Principle

We need to follow our end of the deal: be conservative in what you [send]

. If we do, we maximize the chances that everything works together.

Validating our HTML is part of that. Producing semantically-meaningful markup is another.

URLs: Links and Images

We have seen two contexts where we can give a URL in HTML:

<a href="http://www.sfu.ca/">SFU</a> <img src="http://example.com/img.jpg" alt="a group" />

… and there are a few more that we'll see later.

URLs: Links and Images

The URLs that start with a scheme/protocol (like http://) are absolute URLs.

These indicate where the content is on the web (or elsewhere with another protocol), and take you to the same place no matter where you start on the web.

URLs: Links and Images

The other option is relative URLs which indicate a location relative to the URL of the current page.

We have actually seen one of these:

<img src="group.jpg" alt="a group of people" />

URLs: Links and Images

There are a few things you can do with relative URLs

Resources in the same folder/directory as the .html file: just give the file name.

<img src="group.jpg" alt="a group of people" />

That refers to the image group.jpg in the same folder as the HTML file.

URLs: Links and Images

A relative URL can move into a folder: suppose we have an .html file beside a directory images and want to refer to an image file in there.

Give the name of the directory, slash, and the name of the file:

<img src="images/vacation.jpg" alt="our trip" />

URLs: Links and Images

Or, if we create a directory named courses for some of our HTML and put a file cmpt165.html in there, we can get to it with:

<a href="courses/cmpt165.html">CMPT 165</a>

URLs: Links and Images

We can also move up a level and out of a directory. The special directory name

means ..go up a level

.

e.g. to go from the cmpt165.html page back up to the menu, one level up in the directory hierarchy:

<a href="../menu.html">The Menu</a>

URLs: Links and Images

Suppose we have files organized like this:

URLs: Links and Images

On cmpt165.html, these make sense:

<a href="math.html">Math</a> <a href="last-semester/geog.html">Geography</a> <a href="../menu.html">Menu</a> <img src="summer/poster.svg" alt="project poster" />

URLs: Links and Images

The biggest benefit of relative URLs: they will work on your computer, and after you have uploaded to the server, and if you upload your pages to a different server.

Absolute URLs aren't as flexible (and thats their strength too: they work the same everywhere).

Both absolute and relative URLs can be used anywhere HTML expects a URL.

URLs: Links and Images

Notes:

- There are never backslashes in URLs, always forward slash:

./ - Case matters:

page.htmlandPage.htmlare different URLs. - Spaces aren't allowed in URLs.

Advice: keep your filenames lower-case and replaces spaces with dash/underscore.

Character References

There are a few characters we have seen with a special meaning in HTML code: <, >, ".

We can't just type those everywhere since they mean start of tag, end of tag, attribute value. What if we want to have them appear on a page?

Character References

HTML character references are used to refer to characters we can't type.

Character references start with

and end with &

. e.g. ;< is the character reference for <

. This HTML:

7 < 10

… appears as:

7 < 10

Character References

Another example:

<p>I like the <code><abbr></code> element.</p>

When displayed:

I like the

<abbr>element.

Character References

These are the characters that have special job in HTML, and it's worth remembering their references:

| Character | Reference |

|---|---|

| < | < |

| > | > |

| & | & |

| " | " |

| ' | ' |

Character References

There are also references for characters you just don't have on your keyboard.

See the Character Reference Chart.

Character References

e.g.

<p>Select File → Open. Olé!</p>

Becomes:

Select File → Open. Olé!

Character References

There are even more characters than these named references exist for. For those, you can use numeric character references.

Character References

Numeric references can refer to any character from the Unicode character set. See the Unicode Character Table.

Unicode is designed to represent all written languages: about 140k characters. This includes math symbols, emoji, etc.

Character References

Named references look like

.&name;

Numeric references look like

.Ӓ

If you need a numeric reference, have a look at a Unicode Character Table or Unicode Character Search.

Character References

For example, this uses the Thai baht symbol, which doesn't have a named reference:

<p>The exchange rate is ฿25 ≈ $1.</p>

The exchange rate is ฿25 ≈ $1.

Character References

Assuming your browser displays like mine, the baht symbol is in a different font because the font used in these slides doesn't contain that character.

The exchange rate is ฿25 ≈ $1.

This can be a problem with fonts on the web: do your users have the same fonts that support the same characters as you?

Character References

Emoji are also Unicode characters. You can copy-and-paste them, or use character references:

😉 👍 🍕 🍕

😉 👍 🍕 🍕

Character References

Some character combinations (in some fonts) have more beautiful combinations: ligatures.

flip fizz official tuft bær

The same text without ligatures:

flip fizz official tuft baer

Character References

Ligatures are generally used automatically by the browser. They are also applied to emoji to create combination that can represent a huge variety of characters

.

Character References

For example, the skin tone modifiers (characters 127995 to 127999) with the waving hand (128075):

<p>👋 - 🏿 - 🏻</p> <p>👋🏿 - 👋🏻</p>

👋 - 🏿 - 🏻

👋🏿 - 👋🏻

Character References

The emoji ligatures

allow very flexible combinations: female astronaut with medium-light skin tone:

- Woman Emoji

- Medium-light Skin Tone

- Zero Width Joiner (≈ please join these)

- Rocket Emoji

👩🏼‍🚀

👩🏼🚀

Character References

Also is used for flags, by encoding

the country code with the Regional Indicator Symbol Letters

. Here, the encoding for C, A (CA = Canada), D, E (DE = Deutschland = Germany):

🇨🇦 🇩🇪

🇨🇦 🇩🇪

Character References

Combining emoji doesn't seem to work everywhere. Here is a separate page of the emoji examples.

Screenshots: Firefox on Linux, Chrome on Android, Firefox on Windows 10, Chrome on Windows 10, Edge on Windows 10.

Character References

Typing these as character references isn't fun, but it's possible. It's easier to copy-and-paste from somewhere else if you can.

<p>Option 1: 🤙🏽. Option 2: 🤙🏽.</p>

Option 1: 🤙🏽. Option 2: 🤙🏽.