Algorithms

Algorithms

We have talked about algorithms throughout the course.

Every program is basically the implementation of some algorithm (even if it's a really simple one).

Algorithms

Some algorithms are fairly unremarkable.

e.g. the assignment 1 day of the year

calculation is straightforward enough. We can implement it if we have to, but probably a few lines with the datetime module would be easier to get right.

Algorithms

Part of programming is coming up with these ad hoc algorithms that solve small problems, or aspects of larger ones.

e.g. in exercise 7, you (probably) realized you can draw a grid by drawing some horizontal and vertical lines. Not the most exciting algorithm ever, but you discovered it.

Algorithms

There are other problems and corresponding algorithms that are more central to computing science. These get more attention, are used more commonly, and are more important to have implemented more efficiently (because they're used a lot).

Let's talk about a few…

Linear Search

A first problem: search. Given a list and a value, find the (first) position of that value in the list.

That's easy enough: we have enumerate to give us position, value pairs from a list. We can scan for the value and return the first position we find it.

def linear_search(lst, val):

for i, v in enumerate(lst):

if v == val:

return i

But we're not done yet…

Linear Search

What if the value isn't found?

Let's make the rule that -1 means not found

.

def linear_search(lst, val):

"""

Return the first position of val in lst, or -1.

"""

for i, v in enumerate(lst):

if v == val:

return i

return -1

What's the running time?

Linear Search

For a list of length \(n\), this has running time \(n\): in the worst case we have to go through the whole list.

That's why this is a linear search: it has linear running time.

Linear Search

Linear search is great, but it's slow if you have a big list and it's the best we can do.

- … if the data is in a list, not some other data structure.

- … if the values in the list aren't arranged somehow.

Binary Search

It turns out we can do better than linear search if the list is in sorted (increasing) order.

The idea will be very similar to the guessing game we have been playing all semester: keep track of the first and last possible position and try to discard half each time around a loop.

Binary Search

Let's build a function to search a sorted list, as I would if I was writing it myself…

We are going to keep track of the first and last possible places the value we're searching for could be, and return -1 if we run out of places to search.

def binary_search(lst, value):

first = 0

last = len(lst) - 1

while first <= last:

???

return -1

Binary Search

At this point, I don't see any way to test the code: there's not enough to handle any actual inputs. But I can start to fill in the loop body, just enough to see the halfway between

value I want to examine:

def binary_search(lst, value):

first = 0

last = len(lst) - 1

while first <= last:

mid = (first + last) // 2

v = lst[mid]

print("mid and v:", mid, v)

return -2

return -1

I'm returning -2 just to avoid an infinite loop…

Binary Search

That should find the midpoint of the list, and look at the value there.

test_list = [16, 20, 21, 22, 28, 100, 200] print(binary_search(test_list, 21))

mid and v: 3 22 -2

So far so good: position 3 is the middle of the list and there's a 22 there.

Binary Search

We can now get far enough to test the find it right away

case:

def binary_search(lst, value):

first = 0

last = len(lst) - 1

while first <= last:

mid = (first + last) // 2

v = lst[mid]

if v == value:

return mid

return -1

test_list = [16, 20, 21, 22, 28, 100, 200]

print(binary_search(test_list, 22))

3

That's correct, but any other value argument would cause an infinite loop.

Binary Search

If we haven't found the value, we can decide which half of the list to continue with: we know (1) we have already looked at lst[mid], (2) smaller values are to the left, and (3) larger to the right.

def binary_search(lst, value):

first = 0

last = len(lst) - 1

while first <= last:

mid = (first + last) // 2

v = lst[mid]

if v == value: # found it at lst[mid]

return mid

elif v < value: # value is after position mid

first = mid + 1

else: # value is before position mid

last = mid - 1

return -1

Binary Search

I'm now reasonably sure the binary search is working:

test_list = [16, 20, 21, 22, 28, 100, 200] print(binary_search(test_list, 21)) print(binary_search(test_list, 17)) print(binary_search(test_list, 16)) print(binary_search(test_list, 200))

2 -1 0 6

Binary Search

Let's work through how binary_search does its search in this case:

test_list = [16, 20, 21, 22, 28, 100, 200] print(binary_search(test_list, 21))

Binary Search

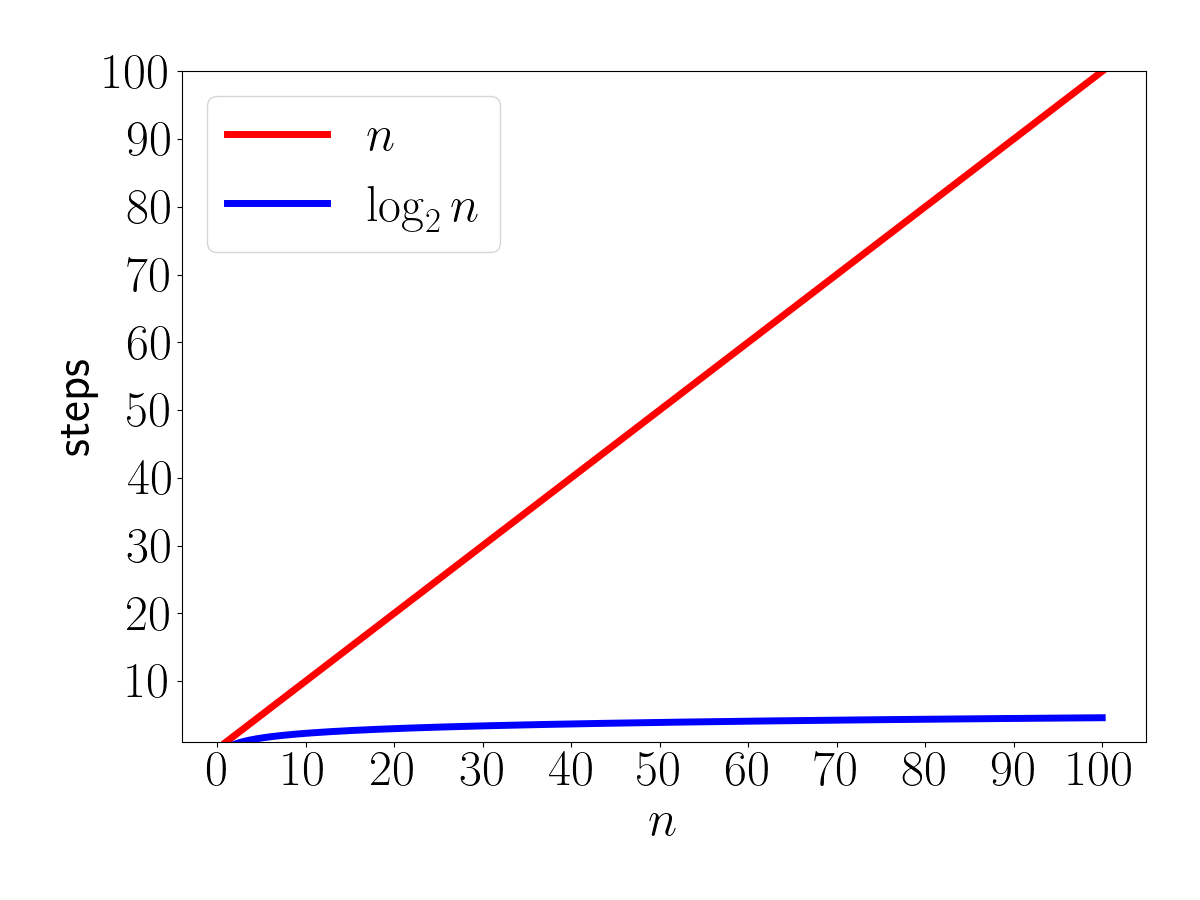

Running time of binary search?

The logic is the same as the guessing game: we're cutting the problem in half with each iteration. The number of times we can divide \(n\) by 2 until we're down to only one option is \(\log_2 n\).

So, search in an unsorted list: \(n\). Search in a sorted list: \(\log n\).

Binary Search

Remember how differently these running times grow.

Sorted Lists

But if we want to add something to our list, it's more complicated than just .append: that puts the element at the end, but if we want to keep the list sorted, we need to put it in the correct sorted location.

Inserting into a sorted list takes running time \(n\): we have to move some list items from position p to p+1 until we have made space for the new value.

Sorted Lists

But if we want to create a sorted list of \(n\) elements, we can just build the unsorted list (running time \(n\)) and then sort it (\(n\log n\), effectively converting the unsorted list to a sorted list).

So the total running time of building a sorted list: \(n + n\log n\). We keep only the highest-order term: \(n\log n\).

Sorted Lists

The running times in summary:

| Operation | Unsorted List | Sorted List |

|---|---|---|

| Search | \(n\) | \(\log n\) |

| Insert | \(1\) | \(n\) |

| Create | \(n\) | \(n\log n\) |

So, which is better? It depends what you're doing. There's a reason we have both options.

Sorted Lists

In some sense, a sorted list is an entirely different data structure than a normal

list: we can search it quickly but it's harder to insert.

The other similar option we have seen: sets. If you don't care about order or duplicate values, sets promise running time \(1\) for search and insert (and therefore \(n\) to build a set with \(n\) elements).

Sorted Lists

Tradeoffs like this are common when selecting a data structure.

We might have choices between speed of various operations, or speed vs simplicity, or memory usage vs speed, or … .

Sorting

We have seen sorting be useful in several ways.

It was mentioned for the repeated characters

problem, but now we can actually write it. The set-based implementation is still a lot easier to get correct, but using the set to do all the work feels like it leaves too many mysteries.

def has_duplicate_chars_1(word):

chars_set = set(word)

return len(word) != len(chars_set)

Sorting

Out original implementation had running time \(n^2\):

def has_duplicate_chars_2(word):

n = len(word)

for p1 in range(n):

for p2 in range(p1 + 1, n):

if word[p1] == word[p2]:

return True

return False

Sorting

This one should have running time \(n\log n\). It relies on the fact that after sorting, duplicates will be adjacent:

def has_duplicate_chars_3(word):

characters = list(word)

characters.sort()

for p in range(len(word) - 1):

if characters[p] == characters[p + 1]:

return True

return False

All of these implementations produce exactly the same results, with very different running times.

Sorting

In a pragmatic sense as a Python programmer, there's probably one way you should sort a list:

the_list.sort()

The built-in sorting implementation is very carefully tuned to perform well in various situations and promises \(n\log n\) running time in the worst case. (It also promises \(n\) steps if given an already-almost-sorted list.)

Sorting

Sorting is important enough that we shouldn't just leave it to an opaque method call.

There are several sorting algorithms that have running time \(n\log n\), but they are (somewhat) complex. We'll focus on one that has running time \(n^2\).

That means it will be slower on large lists, but it turns out to generally be faster on smaller lists (often something like \(n<40\), depending on the details).

Insertion Sort

We will look at the insertion sort algorithm.

The idea: we'll grow a sorted

part of the list. One element at a time, we'll figure out where to put it (insert it

) into the sorted part. By the time we insert every element into the sorted part, the whole list will be sorted.

Insertion Sort

e.g. part way through the sorting, we might have a list in a situation like this:

[3, 8, 9, 12, 7, 2, 15]

The first four elements ([:4]) are sorted. We want to get the next element (the 7) into the sorted part.

[3, 7, 8, 9, 12, 2, 15]

If we can do that, slightly more of the list ([:5]) is sorted.

Insertion Sort

An observation: we can always say the first element is sorted

. That is, if we look at only the first one-element sublist, it's sorted.

e.g. in this list,

[6, 2, 7, 9, 1, 10]

… the prefix [6] is already sorted because every length-1 list is.

Insertion Sort

Now, we just have to grow the sorted prefix.

The idea: we'll look at the next

value past the already-sorted prefix. We'll swap it with the value before it until we find a value smaller than it, or get to the start of the list.

Insertion Sort

Or in a diagram, mid-insertion-sort, we'll have a situation like this:

Insertion Sort

e.g. to insert position 4 (the 7) here,

[3, 8, 9, 12, 7, 2, 15]

… we move it like this:

[3, 8, 9, 7, 12, 2, 15] [3, 8, 7, 9, 12, 2, 15] [3, 7, 8, 9, 12, 2, 15]

Finally, when we compare with the 3, we notice 3 <= 7

Insertion Sort

Side note on another common Python idiom: this assignment statement,

b, a = a, b

… is used to swap the value in two variables. It does a tuple-assignment of (a, b) into the variables b, a.

Insertion Sort

To move the value from lst[to_insert] into position,

pos = to_insert

while pos > 0 and lst[pos - 1] > lst[pos]:

lst[pos], lst[pos - 1] = lst[pos - 1], lst[pos]

pos = pos - 1

So, as long as there's something smaller than the value we're moving to its left, swap the values at pos-1 and pos. Move left along the list until it's into position.

Insertion Sort

Now, all we have to do is repeat that process for every value in the list.

def insertion_sort(lst):

"""

Sort the list in-place using insertion sort.

"""

for to_insert in range(1, len(lst)):

pos = to_insert

while pos > 0 and lst[pos - 1] > lst[pos]:

lst[pos], lst[pos - 1] = lst[pos - 1], lst[pos]

pos = pos - 1

Insertion Sort

I promised running time \(n^2\) for insertion sort. Is it?

for to_insert in range(1, len(lst)):

pos = to_insert

while pos > 0 and lst[pos - 1] > lst[pos]:

lst[pos], lst[pos - 1] = lst[pos - 1], lst[pos]

pos = pos - 1

In the worst case (a reverse-sorted list), the inner loop will have to go all the way back to p==0. That means the total steps will be:

which is running time \(n^2\).

Insertion Sort

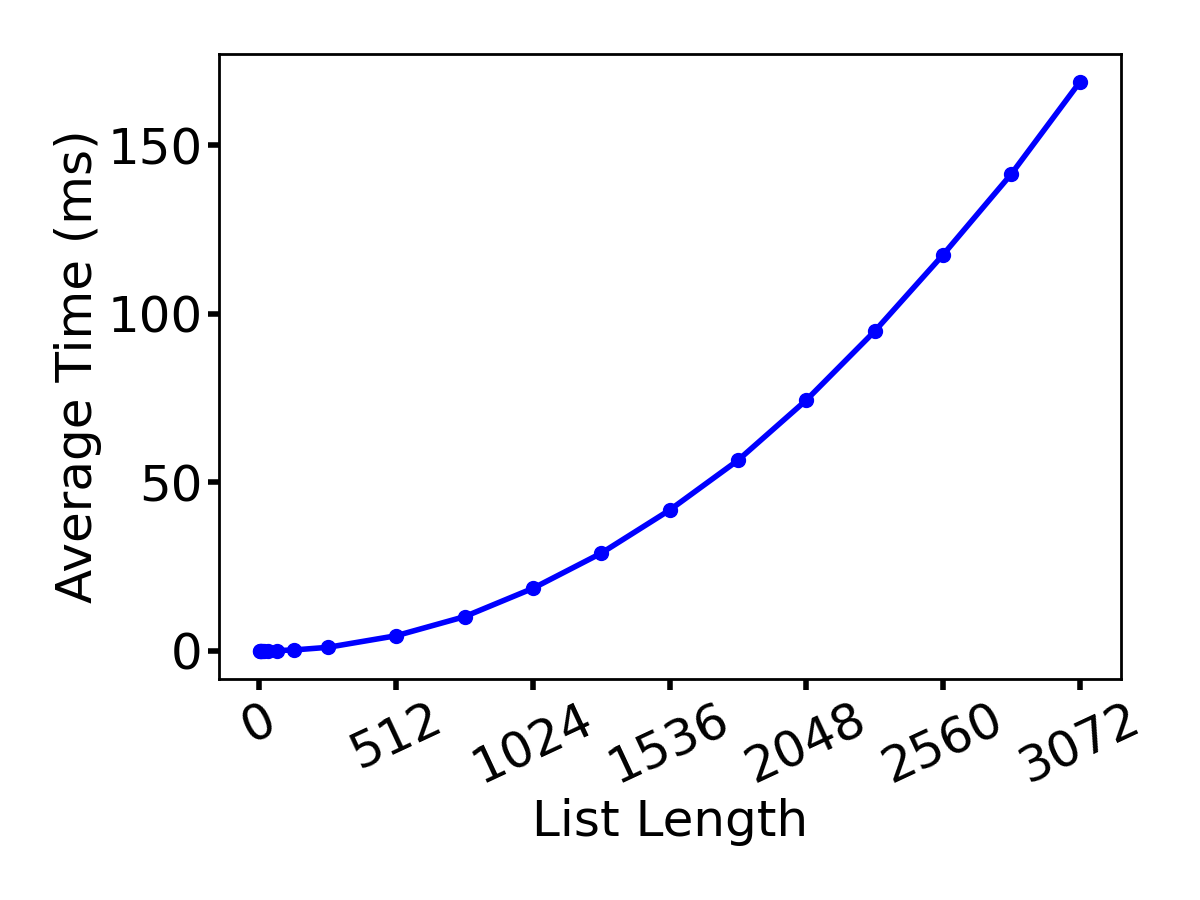

I decided to not trust in the algorithm analysis and do some science. I timed with time.monotonic_ns. Roughly:

for length in lengths:

t = 0

for r in range(reps):

lst = random_list(length)

st = time.monotonic_ns()

insertion_sort(lst)

en = time.monotonic_ns()

t += en - st

print(l, t/reps)

The results?

Insertion Sort

It certainly looks \(n^2\)-like.

Insertion Sort

Let's work through a full example and sort this.

[3, 7, 12, 1, 15, 10]

Other Sorts

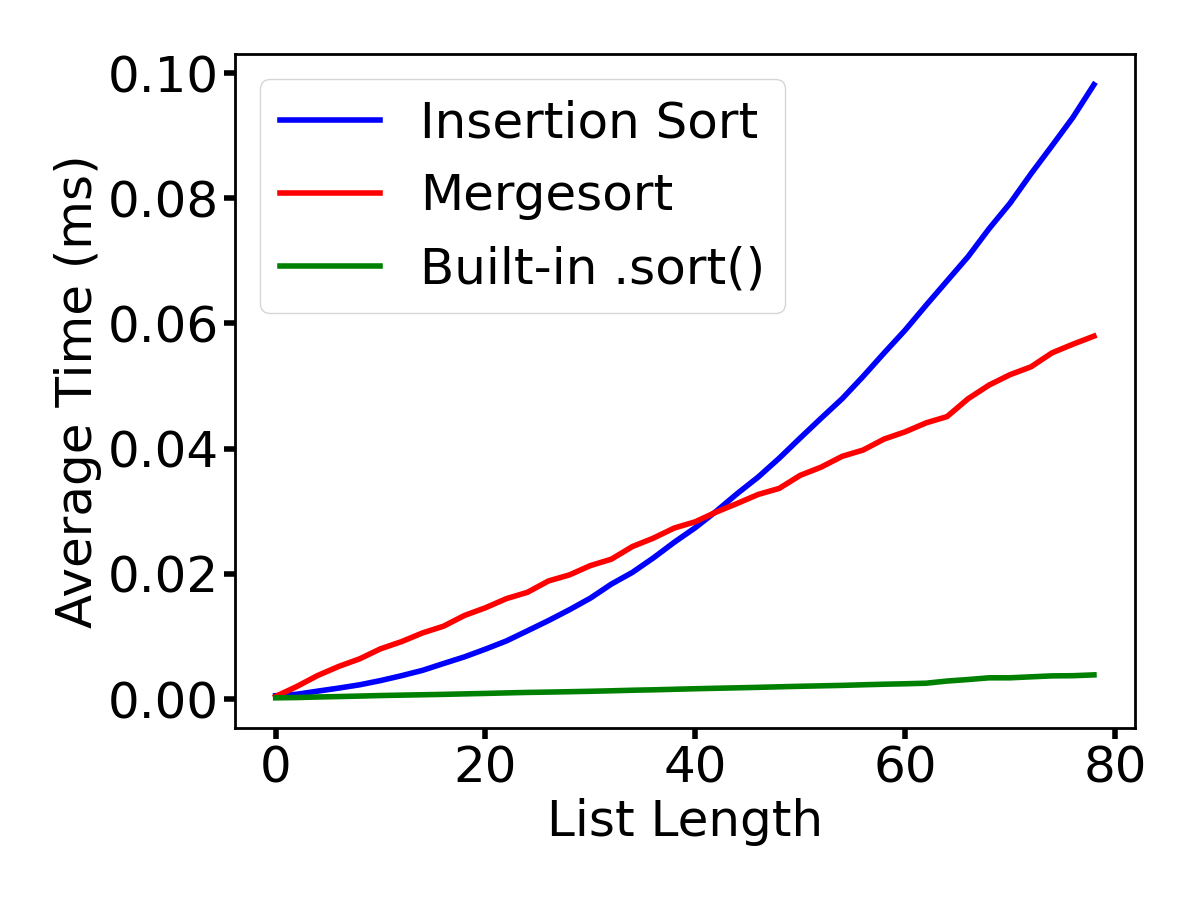

As mentioned earlier: there are several other sorting algorithms, and it's possible to do it in \(n\log n\), which is much better than insertion sort's \(n^2\) for large \(n\).

We won't worry about those algorithms in this course, but their basic pseudocode isn't too bad (as long as we skip a few details that make actual implementations easy to get wrong)…

Other Sorts

The merge sort algorithm is roughly:

- Take the list of \(n\) elements and look at it as two halves: the

left

half with elements \(0\) to \(n/2-1\), and theright

half with elements \(n/2\) to \(n-1\). - Use merge sort to sort the left half.

- Use merge sort to sort the right half.

Merge

the two halves: work through each, taking the smallest from either side until you run out of values.

Other Sorts

Merge sort has running time \(n\log n\) in the worst case. It actually runs in \(n\log n\) in every case: already sorted, reverse sorted, randomly arranged, … .

But for an already sorted (or almost-sorted) list, insertion sort actually only takes \(n\) steps because the \(n\) insertions are all very fast.

Other Sorts

The Quicksort algorithm is roughly:

- Choose an arbitrary element of the list and call it the

pivot

. Partition

the list into elements smaller than the pivot, and elements larger than it.- Use Quicksort to sort the smaller partition.

- Use Quicksort to sort the larger partition.

- Re-combine the smaller, pivot, and larger.

Other Sorts

Quicksort is \(n\log n\) if you pick reasonably good pivots (i.e. kind of near the middle of the values).

If the choice of pivot is bad (e.g. always the smallest element), it ends up having \(n^2\) running time.

Other Sorts

Also, insertion sort tends to be faster than both merge sort and quicksort for smaller lists (somewhere up to 40–80 elements).

So again, there's a tradeoff that might be made, depending on the details of the problem.

Also again, the built-in .sort() method handles all of these very efficiently.

Other Sorts

I tried my own mergesort implementation, our insertion sort, and the built in list .sort():

Other Sorts

Likely takeaway lessons:

- Running times being better/worse is about large

\(n\). For small\(n\), there might be more to the story. - There is generally no

best

solution: just the best for a particular circumstance. - Understanding algorithms for important problems (like sort, search) is important.

- … but people have probably put a lot of time into implementing them better than you could: look for a method/library implementation.